The IoT technology landscape is increasingly being defined by its ability to address large numbers of devices in increasingly inhospitable environments by virtue of slimming down the features and functionality of the offering to make it more appropriate. Last year, we at Transforma Insights published a report on what we termed the ‘Thin IoT stack’. The report examined the arrival of a set of technologies across the IoT stack that are specifically aimed at coping with dealing with the constraints of power, location, space, processing and several other factors that will be increasingly common in a large volume of IoT deployments. The implications of this shift will be felt widely across all aspects of how IoT is deployed, says Matt Hatton, founding partner, Transforma Insights.

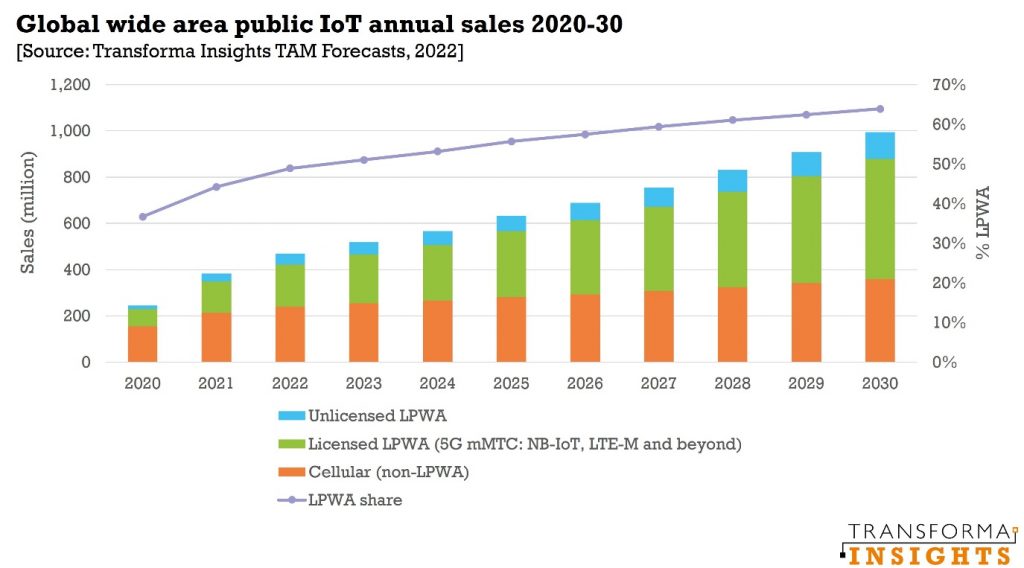

Wide area connectivity for IoT is increasingly defined by the arrival of technologies to overcome constraints, particularly battery life. The raison d’etre of the Low Power Wide Area (LPWA) technologies is to operate where there are constraints on the availability of power. There is also a lot of hype around currently about the potential for low earth orbit (LEO) satellites to address IoT, with many high profile announcements and several partial constellation launches, but as yet precious few customers. As illustrated in the Transforma Insights IoT Forecast Highlights page, LPWA technologies (both licensed NB-IoT/LTE-M and unlicensed such as LoRaWAN) will account for 64% of all new public network connections in 2030.

Local area networking is also getting in on the act. Historically Wi-Fi was the dominant option, at least for domestic connectivity. We expect Thread, off the back of the standardisation of the Matter smart home interoperability protocol, to become increasingly widely adopted. Anyone not already working with Thread/Matter will need to move quite quickly to do so.

The choice of protocols will also be affected by the constraints on IoT deployments. At the Transport Layer, most deployments will choose between Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP), both of which are part of the IP standard. TCP is more complex because it is a ‘connection-oriented’ protocol, meaning that it will seek to establish two-way communications with the receiver, deliver data packets in the correct order and to resend any lost packets. UDP is ‘connectionless’ meaning that it will simply send the data packets without consideration of whether the recipient is ready and will not seek to confirm receipt or retransmit lost packets.

As a result, UDP is a lighter protocol and therefore more applicable for constrained IoT. Riding on top of these protocols are two messaging protocols, MQTT and CoAP. Both were designed to make very efficient use of network resources in constrained environments, but CoAP is inherently more appropriate for constrained environments, being based on UDP. MQTT is more secure and provides more of a guarantee on delivery, but it is a chattier protocol.

Another aspect closely tied with the choice of protocols is security. Constrained IoT deployments will rely on CoAP/UDP, but that has a more limited set of security capabilities than TCP-based deployments. This creates challenges for delivering to the cloud, and specifically for the requirement for ‘cloud connectors’. The likes of AWS and Microsoft Azure will not accept DTLS-based security meaning that constrained IoT devices, i.e. the majority of IoT devices, need some kind of protocol conversion for them to be delivered to the cloud.

As more and more IoT applications move into the cloud this need only increases. The solution is a cloud connector, which handles secure delivery to a network element and then protocol conversion to then deliver to the cloud. Ericsson has built this kind of functionality into IoT Accelerator (Cloud Connect) and operators such as EMnify, Telefonica and Verizon have built the necessary functionality also.

Device management is another arena where constrained IoT becomes increasingly an issue. With unlimited bandwidth it’s fine to rely on proprietary device management based on MQTT messaging, or even very heavy protocols like TR-069 to handle firmware updates and so forth. In constrained deployments there is a much greater requirement for a thin device management protocol. Lightweight M2M (LwM2M) is the clear candidate here. While a lot of devices feature some rudimentary variant of LwM2M today its real adoption has been very limited. We expect this to grow quite rapidly.

Edge computing is another aspect of IoT that is almost defined by the requirement to overcome constraints. In this case, it is the requirement to process increasingly complex sets of data in real-time (or near real-time), particularly in the context of artificial intelligence (i.e. putting the decision-making onto or near to the edge device). Here the constraint is the fact that accessing compute resources in the cloud will slow down significantly the overall processing time, meaning that compute capabilities need to be placed on the edge device. This aspect of constrained IoT actually means smarter, rather than dumber, devices.

It should be noted that 5G helps significantly with overcoming the latency and bandwidth limitations, in circumstances where the use case justifies the additional hardware cost (and probably connectivity cost too). But this also helps to stimulate another form of edge computing: Mobile Edge Computing (MEC), i.e. the requirement for greater processing at the edge of the network. Putting the ‘smarts’ of the IoT application and/or AI at the edge of the network allows for some degree of aggregation and easier management, and combined with 5G low latency for connecting to the edge device, will be optimal for many use cases.

The requirement for large amounts of on-device processing is atypical, however. In most cases the IoT use case will want to minimise data processing and anything related to running the application/device, in order to reduce the cost of the device. This has triggered a requirement for embedded operating systems such as Amazon FreeRTOS, RIOT and TinyOS with very small footprints.

The final element – and some would say the most critical of the IoT solution is the application. Here there is an overwhelming need to adapt the application to suit the constraints in which it is being deployed. Having highly ‘chatty’ applications will cause havoc for low power devices, or those using connectivity technologies able to only send a few messages per day, as with store-and-forward LoRaWAN over satellite, for instance.

The key macro trend is all of this is the increasing requirement for all of the constituent elements of the application to be optimised with each other, including hardware (a topic not even touched on in this article), connectivity, protocols, device management, data processing, networking and the actual application itself. The priority for anyone building an IoT application is to ensure that all these elements are optimised to work with each other. This is easier said than done and points quite clearly to a much greater requirement in future for the supply of these aspects to be done in a coordinated way.

This greater coordination might mean that more of the building of IoT drifts towards systems integrators, but most of the mass market of IoT solutions just won’t be able to afford the associated cost. Alternatively, participants in the IoT value chain need a function (perhaps a ‘consulting-lite’ capability) that works with the customer to optimise the solution, or a new category of IoT solutions vendors are needed. Or vendors need some kind of optimisation function which curates a set of interoperable application elements and ensures that they work well with each other. This type of function is envisaged in things like Deutsche Telekom IoT’s IoT Solution Optimiser or the recently announced Siemens Xcelerator platform.

This coordination will inevitably help with one of the greatest headaches of deploying IoT: fault resolution. With disparate elements that aren’t optimised together it’s often hard to avoid a blame game between vendors in the event of faults. An optimised solution and ideally a single point of contact (i.e. the optimiser) should reduce issues and result in swifter resolution. While the concept of the ‘single throat to choke’ is a bit cliched, it is becoming increasingly important. Contrast this with the idea of the ‘one-stop-shop’, about which this analyst has always been sceptical. The benefits of a single bill or ease of buying multiple elements together have never been real differentiators. The ability to resolve faults in critically interconnected elements is.

This article draws on research from several reports available as part of the Transforma Insights Advisory Service. If you would like to hear more about this topic, Matt Hatton is speaking at the MEF Connects Digital Transformation event. See our events page for more details.

The author is Matt Hatton, founding partner, Transforma Insights.

Comment on this article below or via Twitter: @IoTNow_OR @jcIoTnow